When it comes to supporting the UK industry’s cause, Charles Bourns is one of a kind. Michael Barker hears all about his remarkable career

Charles Bourns is, in many ways, Mr Poultry. There are very few individuals indeed who can claim to have done as much as the West Country farmer to promote the agenda of the industry, both politically and to consumers, and push forward the interests of the nation’s producers.

Bourns – who deservedly picked up the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2025 National Egg & Poultry Awards – was born in Bristol to non-farming parents, but he did have connections to the industry through a grandfather and uncles that farmed in Devon and Ireland respectively. “I used to go out there on holidays and farming got into my blood,” he recalls, pointing out that his three brothers instead followed careers as a lawyer, banker and dentist.

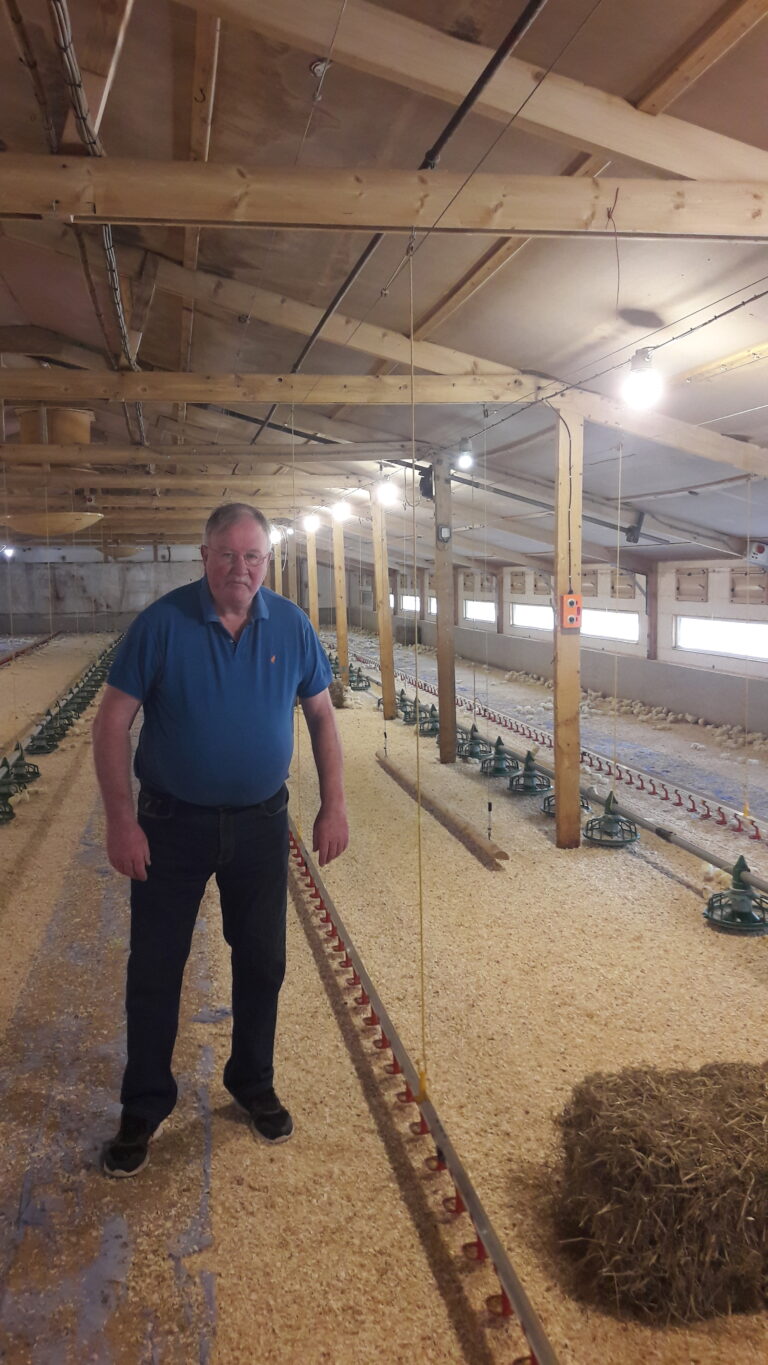

Upon leaving school, Bourns pursued his dream by becoming a farm manager in Sussex, before moving into the animal feed trade and renting a farm on the side. It wasn’t until the age of 40, though, that he bought the land in Gloucester that he has produced broilers on ever since. Northcotts Poultry had 99,000 birds in those days, with 82,000 more in Frome and 27,000 in Trowbridge, both on rented land. The business has changed a bit over the years, but with the support of Bourns’ son James it has recently updated its sheds to make it fit for modern production. His other son, Patrick, is a free range producer, near Stow on the Wold.

Industry titan

That farm purchase back in 1989 coincided with the start of Bourns’ long and storied career as an industry advocate, which began when he became vice chairman to James Hook of the new NFU central region, as well as their poultry meat representative. His journey with the union saw him go on to become vice chair and then chair of the main NFU Poultry Board.

Over the coming decade Bourns learnt plenty about the nuances of politics and trade, travelling far and wide to represent the industry. He crossed Europe from Portugal to Italy, and went as far afield as China and Brazil.

It was during that period that he realised the UK was lagging behind when it came to building its reputation, both domestically and abroad. He particularly recalls a trade meeting in London in the early days, where a delegation from Brazil was promising UK buyers the moon on a stick in terms of poultry meat supply, and realised that Brits had to up their game when it came to self-promotion. “The Brazilians made the whole of their industry sound so sexy and wonderful, and I came back to the NFU and I said ‘we’re going to have to do something to promote British chicken’,” he says.

Never one to issue words without deeds, Bourns swung into action to gather support for his plan. With the help of Grampian, Hook’s, Nigel Joice and others, in 2004 he took on a challenge set by the British Poultry Council of raising a quarter of a million pounds from the industry to put together British Chicken Marketing, an organisation to promote home-grown chicken. “At the time, the British chicken market was around 15 million birds, but falling, and with a lot of imports on the shelf. And nothing was being done to promote them,” he says.

With the likes of Bourns, Patrick Hook, Joice, Peter King, and other industry luminaries as directors, British Chicken Marketing was launched in 2005. “The industry wasn’t overly keen on it at first, but we did reverse the trend from falling sales into increasing sales, and it also improved our relationship with the chicken buyers,” he recalls. “We got it off the ground and it did very well.”

Promoting poultry

It’s a source of clear frustration to Bourns that the organisation he helped establish is not still running to this day. He describes the industry’s decision to stop supporting what was a highly successful endeavour as a “big mistake”, pointing out it had done fantastic work in reinforcing the benefits of British chicken to consumers. “I got very frustrated but there was nothing I could do about it because I didn’t have three-quarters of a million pounds,” he says. “If I won the lottery tomorrow I’d go and do it again, because I think it’s the right thing to do.”

Bourns believes marketing is essential to a healthy industry, and worries about the complacency of simply expecting the public to blindly support local production. “I always say to people that you can have the best car in the world sat in the garage, but if you don’t tell anybody about it they won’t know,” he warns.

It can be difficult to understand why whole-industry marketing has waned in recent times, but Bourns puts it down to the very narrow margins that many suppliers operate on, as well as the fact that a lot of chicken is sold purely on price. “You can buy a large chicken for £5.49, and the same piece of beef or lamb costs you four times that price,” he notes. “So it’s very good value for money. And a huge number of other products are bought off the back of it – stuffing, sauces, all sorts. It means the supermarkets value it. It’s a good product.”

Bourns has never been afraid of flying the flag for Britain, but he is by no means an international isolationist either, and bemoans the ongoing negative impacts of Brexit. In particular, he is mystified why anyone would want to walk away from a market with half a billion customers. “It’s just a travesty,” he says. “We never should have got out.”

The NFU was only one part of what you might call Bourns’ public service to the poultry industry. His work with the farmers’ union took him to Brussels, where we went on to become president of farming and agri-cooperative group Copa Cogeca, and president of the European Commission’s working group on eggs and poultry meat. On a more local level, he’s been chair of the Southwest Chicken Association, a role one suspects he approached with as much zest as anything on the international stage. He’s also currently chairman of the National Fallen Stock Company.

Bourns has many tales of his work fighting the industry’s corner, such as the time that IPPC legislation was first introduced. “The amount of aggravation and fighting and discussion we had around that,” he recalls. “When they first brought it in they wanted to charge £18,000 a farm. It ended up around £1,400 a farm, but that was a lot less than they wanted. My diatribe on why I thought it was bad… I didn’t stop for an hour and a half, filibustering at one of the meetings in Shaftsbury Avenue. I don’t know how I kept going!”

Earning respect

So what drove this desire to contribute so handsomely to the common cause? “My family always believed that you’re better off getting involved rather than standing on the outside,” he explains. “My mother and father started a hospice in Bristol, my father was on the regional health board, my brother Robert was president of the Law Society, and my elder brother was in The Prince’s Trust. We’re a family that tends to get involved rather than sit on the outside and moan and groan. My mother brought us up as children to believe that a camel was a horse designed by committee! We tend to be fairly independent in our thoughts, but we try to get involved and get things done.”

The impact of family in Bourns’ life is also tinged with sadness. His wife, mother and all three brothers died from cancer at various points over the years, their lives all cut short long before their time. It makes the question of whether retirement is coming soon particularly poignant for Bourns: “Unfortunately there’s nobody in my family that’s ever retired,” he says. “My father was 75 when he died, and all of my brothers have gone too.”

Bourns’ son James has now come home and is running the farm, growing chicken for Marks & Spencer. That’s clearly a source of satisfaction, but he bats away the question of what he’s most proud of during his career. Instead he is simply grateful to be respected and have made a contribution to the industry. “I’m well known for being fairly straight, down to earth and with an honest opinion,” he says with remarkable unpretentiousness. “I was brought up in a family where having respect was important. I’m in the Masons in Bristol and I still meet people there that remember my father fondly. That’s the legacy right there. Whether I retire or not, I’m the last one standing [in the family]. I’ve had a heart operation, I’ve had new valves, they spent two years trying to get my legs right… I’m looking at the daisies from the right side!”

For all his individual achievements, Bourns is lavish in praise of those who have gone on the journey with him. “You don’t receive a lifetime achievement award without having good people that work with you and help you along the way,” he insists. “You can’t do it all by yourself.”

He describes the recently deceased industry legend Aled Griffiths as a mentor, and one of three people who he particularly leaned on for advice alongside James Hook and Stephen Hay. “When you’ve got ideas, not all of them are sensible and you need someone that you can ring up and ask what they think,” he says. “Everyone needs people in their life to give you an unbiased, unpolitical, thoughtful answer. Aled was fantastic, and took me to Europe and introduced me to all those people. Stephen was blinking good – when I was selling animal feed he was supportive and helped get money together from the industry. And James – when we were in tremendous financial difficulty he came along and rented the farm, which meant we were in a position to sort ourselves out. I’ve been very lucky.”

Bourns is keen to make sure that he can still make a valued contribution and stay relevant. “New people come in and they do one of two things – say exactly the same thing as I was saying 20 years ago, or they come up with new ideas,” he smiles. “If go to a local meeting, I think they still value my interjections, but it’s a younger industry now. They don’t need a 77-year-old to go on the television to represent the industry when they’ve got plenty of young people coming through and doing a good job.”

He’s not one to tell the next generation what to do, but he does urge them to do more marketing and find the time to promote British product.

Bourns is proud of how far the industry has come in the time he’s worked in it, admitting the first farm he ever set foot in was “horrible”. He wishes the industry would get more credit for the way it has changed, in particular the profound level of bird welfare improvements that have been made over the years. It ties in, again, with his desire to highlight to consumers the high quality of British product and hit back against what he feels is the animal welfare lobby’s relentless campaign to smear the sector.

One imagines Bourns will never want to stop doing his bit, and it doesn’t matter to him whether that is on the big stage or the most local of levels. It’s been his life’s mission, and alongside playing his part in feeding the nation, he been outstandingly good at it.